by: Hector Paez

No gym conversation is complete without mentioning protein. While the concept of consuming protein if you’re a strength athlete is not foreign or debatable, the manner and method for consumption is often argued. Some will go as far as to say that if you aren’t already drinking your protein shake immediately after that last rep of dumbbell curls hits the rubber matting on the gym floor, you’ve basically thrown away the entire workout. While I’m sure the majority of people now know that the infamous “anabolic window” is more like an anabolic barn door, there’s still a few more things we can learn about how protein contributes to gaining muscle so we can be just a little more optimal with the way we structure our diet.

Firstly, let’s set a basis and understand some simple terms so we can be on the same page. We use the term “hypertrophy” to describe when a muscle grows in size. Hypertrophy happens through a process called muscle protein synthesis (MPS) in which protein accretion over time subsequently results in a bigger, stronger, more jacked you. What’s important to note is that MPS is not an on/off switch, it’s constantly going on. But if so, why aren’t we all just infinitely getting more muscular?

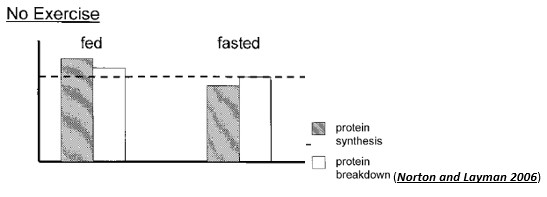

Enter protein degradation, MPS’s arch nemesis. As the name implies, protein degradation is the process of protein breaking down. Whether hypertrophy takes place or not is at the mercy of the net result of protein synthesis over breakdown. We call this struggle between anabolism and catabolism the “protein turnover ratio” and your gains are contingent on keeping it in a positive state.

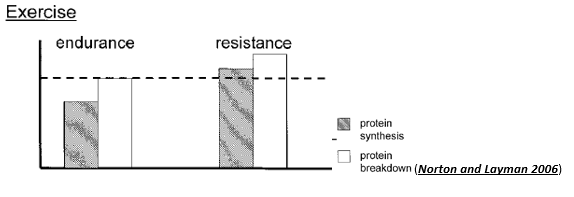

So how do we accomplish that? Disciples of the Broly Bible would have you believe that to stay away from impending catabolism you should definitely stay away from cardio. Well check the sky for pigs, because they finally got something right (at least partially). Extended long periods of endurance training can inhibit protein synthesis to the point that we have a detrimental impact on protein turnover ratio. Fast glycolysis is one of the primary energy systems used by muscle fibers for high effort exercise lasting from 10 to 30 seconds (think sprints or a challenging set of 12 reps). Extended periods of endurance training can cause a depletion of muscle glycogen, which is the storage form of carbohydrate in the muscle. 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase or “AMPK” is an enzyme that senses the energy state of the cell. Once this enzyme senses low glycogen content, it inhibits muscle protein synthesis by blunting mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) in order to spare adenosine triphosphate (the cells energy currency) and free up energy. By decreasing protein synthesis and leaving breakdown relatively unchanged, we end up with a negative protein turnover ratio.

So as it turns out, all those powerlifters were on to something when it comes to avoiding cardio. Now it’s important to note that short bouts of cardio on days you don’t train the muscles involved probably aren’t going to hurt you much. So don’t let that be an excuse to let your cardiovascular health tank.

What may be surprising as noted in the figure above is that resistance training also leads to a negative protein turnover ratio, this is a result of protein breakdown increasing past the surge in protein synthesis. As it turns out, being in a fasted state also decreases synthesis below the baseline of protein breakdown. So you may be wondering, how on earth do I increase synthesis? The answer is pretty simple, you gotta eat kid! Having a meal increases protein breakdown, but not as much as it swells up protein synthesis. This net gain results in protein accretion.

Now that we have a simple concept in place, we can delve a little deeper as to how we can structure our protein feedings a little better. Proteins are made up of smaller units called amino acids. To keep this within the scope of our conversation, we’re going to focus specifically on leucine. Leucine is an essential amino acid, and the content of leucine in your protein matters.

About 3-3.5 grams of leucine are necessary to stimulate maximum MPS in a single meal. MPS will peak circa 90 minutes after ingestion and plasma level concentrations will stay elevated for about three hours. During this three hour “refractory period” MPS cannot be stimulated again. Hence it would make sense that if our goal is to stimulate MPS we should be having a bolus of protein containing 3-3.5 grams of leucine every 3-5 hours. Research has shown that having one feeding of protein that meets this leucine threshold results in more MPS than having multiple feedings per day that each don’t meet the aforementioned leucine content. Now what’s important to take away from this is that one protein feeding per day is not more beneficial than multiple feedings. It is important to conceptually understand that the leucine content of your protein feedings matters more than the frequency of your meals.

Now at this point I hope I haven’t bored you to death, but there’s one more important topic we need to discuss if you’re to be graced with the gains of peace and allowed entrance into Valhalla. All protein is not created equal, different sources of protein have different leucine contents and thus varying amounts need to be used in each meal to achieve our leucine threshold.

For example, whey protein is very high in leucine (12.0%) and only 17-25 grams of whey protein are needed to reach the leucine threshold. Chicken on the other hand boasts a protein content of 7.5% and thus 27-38 grams of protein are needed in order to reach the leucine threshold. Now this isn’t to say that you should always pick whey protein over chicken, but it does shed light on the fact that the amount of protein needed varies by the source.

Now that you know a little more about how to structure your intake, I hope you keep protein turnover ratio positive my friends.

Cheers,

Stay connected!

Here’s how to follow us:

Instagram: @GentlemanAndMeathead

Facebook: Facebook.com/GentlemanAndMeathead

Twitter: @ClassyMeathead

Enjoy this article? Give it a share with your fellow dapper meatheads!

References

Norton, L. E., & Layman, D. K. (n.d.). Leucine regulates translation initiation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle after exercise. The Journal of Nutrition. (2006)

[2] Arnol, MA., et al. “Protein pulse feeding improves protein retention in elderly women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. (2002)